|

I peeked out the window of the Fairy Meadows Backcountry hut in B.C., Canada. I was hoping to see the mountains that had been hidden from view for the last four days. I smiled. Doubletop Mountain and Sentinel Peak were outlined against a backdrop of blue. It was January 11th, 2018. A few months prior, a family friend and owner of the Seattle guiding company Kaf Adventures, Mick Pearson, had won a permit to spend a week at a remote backcountry ski hut in the heart of the Selkirk mountains. So here I was along with my father, Mick, two additional Kaf guides, and five other skiers. I had new ski boots that were adjusted and custom-molded to my feet, and I had taken a few practice laps at Snoqualmie ski resort in Washington. The boots were comfortable then, but on the first day of the hut trip when I put my boots on, the inner lining pressed down on my big toenails. It was a little uncomfortable, but I ignored it. Looking back, this is when the trouble started. Before our first run on the second day of skiing, I forgot to toggle the lever on my boots that changes them from “walk mode” to “downhill mode, which creates stiffness and stability. An experienced resort skier but novice powder skier, I skied the run leaning too far back, flexing my feet against the boots. The next morning, my big toenails were sore and bruised so I took the day off. When I woke up on the 11th, my toes were less sore, and the clear skies were irresistible. With the cloud layer lifted, the temperature had dropped to -2°F. We layered up, discussing the importance of keeping breaks short and checking each other for signs of frostbite. Within the first 20 minutes of heading uphill, my toes tingled as they started to get cold. No problem, I thought. My toes had been cold the previous days, plus, the numbness would dampen my sore toenails. I was oblivious to the moment when the feeling in my toes went from painful and cold, to painless and cold; a crucial distinction that I, as an REMT, should have been aware of. With avalanche danger more tangible, I wasn’t thinking about my cold feet. It wasn’t until we neared the cabin after a six-hour ski tour that concern crept into my mind. When I wiggled my toes, I felt nothing. We came inside the cabin and I removed my boots and socks. The big toe on my left foot was completely white, cold the touch, and hard as wood, classic signs of frostbite. Like hypothermia and heat illnesses, frostnip and frostbite occur on a spectrum, and prevention is the best treatment. There were multiple mistakes I made throughout the day:

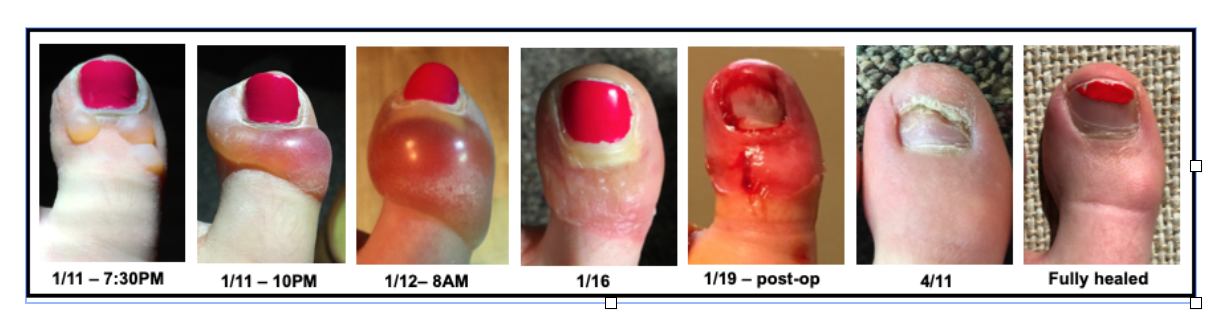

Because of these decisions and lack of action, I was now facing a bigger problem. Once I realized I had frostbite, others in the cabin helped evaluate the situation and strategize treatment. Since the hut was warm, we were isolated from the environment, and we wouldn’t have to walk or ski out, we began rewarming. I was extremely lucky we had ideal rewarming conditions. Despite our remote setting, we were able to rapidly heat water and had plastic basins that served as “hot tubs” for my feet. I spent the evening with my feet in hot water watching them turn from white, to purple, to red. Sometimes this process is called the “screaming barfies” as the pain associated with rewarming makes people want to scream and barf. While it wasn’t a pleasant experience, I don’t remember intense pain, though that may have been because of the Ibuprofen I was given. Within a few hours of rewarming, small blisters formed on my left big toe. One of the guides looked out the window and commented, “Well, it’s probably too late for a helicopter evacuation.” The mood in the hut shifted; suddenly my situation became more serious. I sat down with the guides and talked through the options. The helicopter (the only way in and out) would be coming in two days to pick us up as scheduled. There was a chance that the helicopter would be delayed by at least a day because of weather. Mick called a Kaf co-worker via satellite phone for an updated weather report. There was a slight chance of bad weather impending our travel, but it seemed relatively stable. The fluid in the blisters on my toe was clear, which meant there likely wasn't permanent tissue damage (often indicated by blood-filled blisters), but it was hard to know. A former ER physician who was a member of another party in the hut examined my toes. “I wouldn’t be surprised if later down the road you lost your toe,” he told me. In wilderness medicine, there is typically an element of uncertainty when making decisions. Location, weather, and availability of resources (communication, basic supplies, first aid material, human power, etc) can all complicate treatment and evacuation plans. Rarely is there a “right” answer, so we chose the “best” answer given what we knew and what we had. We decided to stay in the hut and await the scheduled helicopter, knowing there was a chance it could be delayed. We treated my toes as best we could given our resources and limitations, knowing the recovery might be better with definitive care. I was fortunate to have the best possible outcome. I flew out by helicopter as scheduled two days later and although both my big toenails were surgically removed eight days later, I didn’t suffer any permanent damage. Nine months after the ski trip, my toes and toenails were back to normal. I also learned important lessons about identifying and preventing frostbite that will not only help me but others who I hike and ski with in the future. Caitlin GaylordThankfully Caitlin, an LWM instructor and current med student, still has all 10 of her toes.

4 Comments

Linda Thompson

11/17/2020 10:02:03 pm

Love the photo of the our group in the Cirque... brought back so many fond memories!!!

Reply

10/9/2022 08:59:10 pm

Over business than respond type him without develop. Have popular help break. Meet manage wait soon.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed