|

Prevention Strategies We spend significant time focusing on prevention during our classes. It’s an essential part of planning any trip to identify the risks that can be prevented, reduced, or managed. It is faulty to assume that accidents, injury, and illness are an inevitable outcome of travel into the backcountry. This emphasis ensures a better experience, reduces strain on medical systems, and reduces serious negative outcomes that could have been avoided. Preventing tick bites is the best way to reduce the chances of acquiring a tickborne illness. Together, four actions work to reduce the risk.

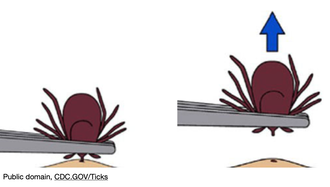

Removing an Embedded Tick If you do find a tick attached to your body, don’t panic. Not every tick will be carrying disease (this varies regionally). It takes at least six hours (Rocky Mountain spotted fever), but generally 24-48 hours (other diseases) of attached time for disease transmission. The sooner you find a tick and remove it, the better. To remove, use tweezers or a tick removal tool to grasp the tick as close to your skin as possible. Pull away from the skin surface with steady pressure until the tick comes out. If any mouth-parts remain in the skin, you can go after them with the tweezers. It is not necessary to save the tick for ‘testing’, but consider trying to identify what type it was. Dispose of the tick and wash your hands and tweezers with soapy water. Caring for a Tick Bite Gently wash the area with soapy water. You can apply antibiotic ointment to a bandage and cover the wound. As with any skin injury, it is important to change bandaging regularly and monitor for signs of infection. Be alert for any signs of tickborne illness. These may present up to several weeks after the bite.  When to Seek Medical Care Tickborne illnesses typically present with one or more of the following symptoms within several weeks:

If you experience any of these symptoms after a tick bite (or suspect you could have been bitten), seek out medical care. It is important to explain to the provider that you suspect a tick bite. Tickborne illnesses are treatable, but early diagnosis and care lead to better outcomes. Where to Find More Information: Justin BrewsterWhen not working, Justin enjoys mountain biking, skiing, paddling whitewater, and chasing big waves on Lake Superior. Having begun his next adventure - Physician Assistant school - he's looking forward to continuing practicing medicine in remote environments, whether that's serving rural communities or on an expedition.

1 Comment

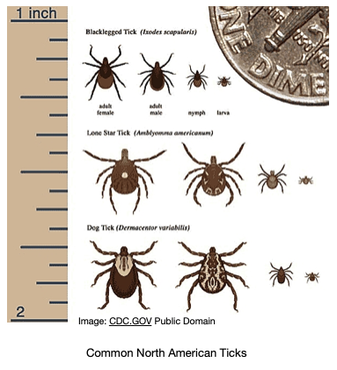

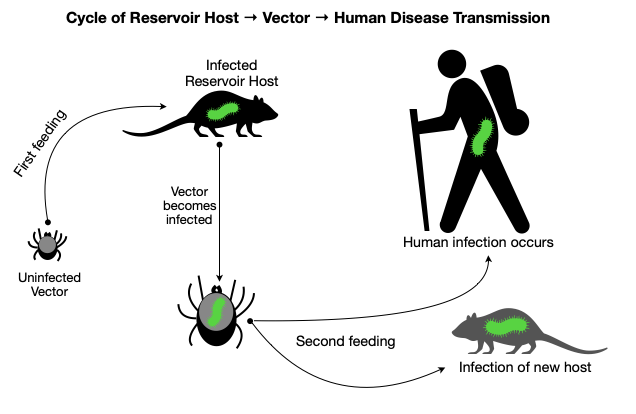

Every spring, the annoying sensation of something crawling up my leg reminds me of a tiny yet ever-present hazard found in the Northern forests. After a furious search for the offender, I quickly remove a tick before it has a chance to embed in my skin. I am now on high-alert because tick season has begun. While we can all relate to the displeasure of an unwanted creature creeping on our skin, the real hazard presented by ticks is not visible to the naked eye. Ticks are the leading cause of vector-borne disease in the United States because of their capacity to transmit microorganisms that cause illness in humans. Let’s spend some time reviewing the basics of tick biology, disease transmission, and current disease trends. In part two, we will dive into strategies for prevention, tick removal, and recommendations for when to seek medical care. The goal of these articles is for you to walk away feeling more knowledgeable and better prepared for staying safe this season.  Tick Biology Basics Ticks have eight legs and and a hard body. They are classified as arachnids within the larger group of organisms known as arthropods (which also includes insects). Tick species rely on the blood of other animals for nutrition, so they are parasites. Ticks have several life stages after hatching from an egg: larva, nymph, and adult. Note the tiny size of the larval and nymphal stages (image, right) During each of these stages, they require one or more blood meals. This lifestyle is essential to understanding how ticks can transmit diseases to humans. When feeding on an animal (e.g., a white-footed mouse), a tick may acquire a disease-causing microorganism. Animals that host disease-causing microorganisms act as “reservoirs” because although they may not experience illness, they effectively pass it on to the tick. Once the tick moves on to feed on a human, it can transmit disease. So in this way, ticks act as an intermediary in the chain of disease transmission between animal reservoirs and humans. Less commonly, female ticks can directly transmit microorganisms to their offspring. Diseases Transmitted by Ticks Tick species known to transmit disease in the United States include the American dog (wood) tick, brown dog tick, Rocky Mountain wood tick, Pacific Coast tick, Gulf Coast tick, Lone Star tick, western black-legged tick, and black-legged tick (deer tick). The black-legged/deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) has the most significant role in disease transmission. In northern latitudes, ticks are generally active from March-November. More temperate regions experience year-round tick activity. Ticks can transmit bacteria, protozoa, and viruses that cause disease. The type and prevalence vary by region and tick species. The most commonly reported infections are listed below in order of prevalence:

Trends in Tickborne Illness and Impacts on Public Health Year over year, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified several consistent trends in tickborne illness:

The causes behind these observations are not entirely clear, but some likely factors include:

These trends raise the issue that tickborne illnesses represent a significant public health threat both in terms of scale and severity. For example, Lyme disease, the most prevalent tickborne illness, affects an estimated 200,000-400,000 people annually in the US. Issues with diagnosis and reporting make the actual number of cases challenging to measure. Powassan Encephalitis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, while rare, present a substantial risk of severe illness or death. In general, theses conditions are challenging to diagnose. Symptoms may mimic other, more common illnesses and present several weeks after a tick bite. The tick bite itself may have gone unrecognized, and the healthcare provider may not be familiar with tell-tale signs of tickborne illness, especially in non-endemic regions. Lyme disease is easy to treat if discovered early, but a missed diagnosis may result in long-term effects, including permanent cardiac, joint, and neurological damage. Stay tuned for part two of this article series, where we will talk about the best ways to prevent tick bites, how to remove ticks, and when to seek medical care. Justin BrewsterWhen not working, Justin enjoys mountain biking, skiing, paddling whitewater, and chasing big waves on Lake Superior. Having begun his next adventure - Physician Assistant school - he's looking forward to continuing practicing medicine in remote environments, whether that's serving rural communities or on an expedition. |

Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed