|

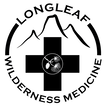

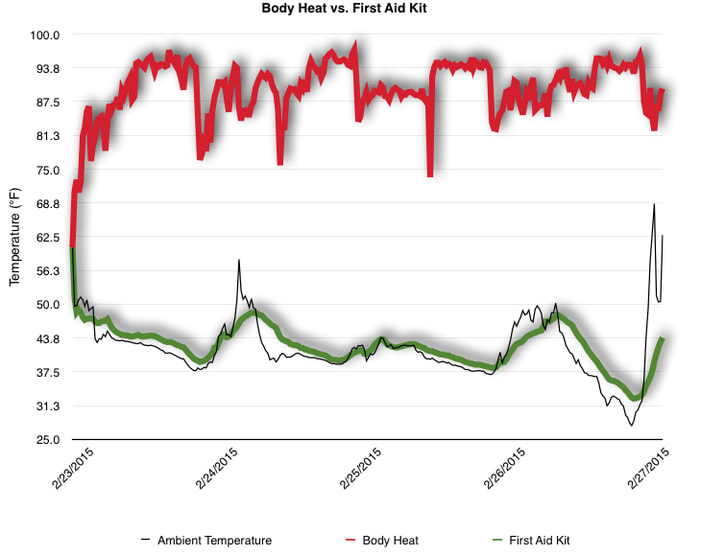

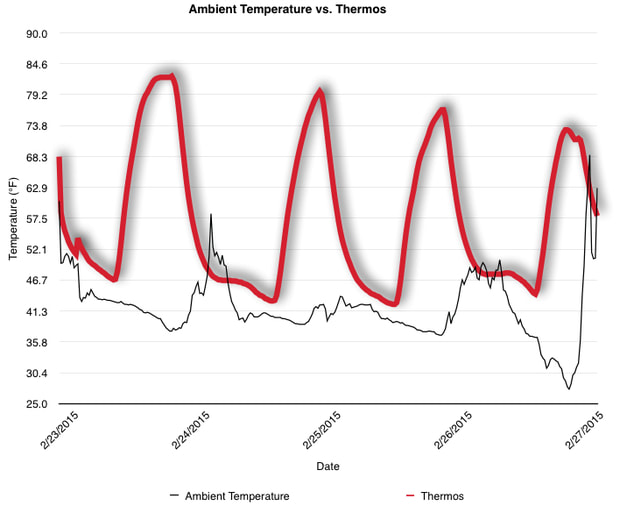

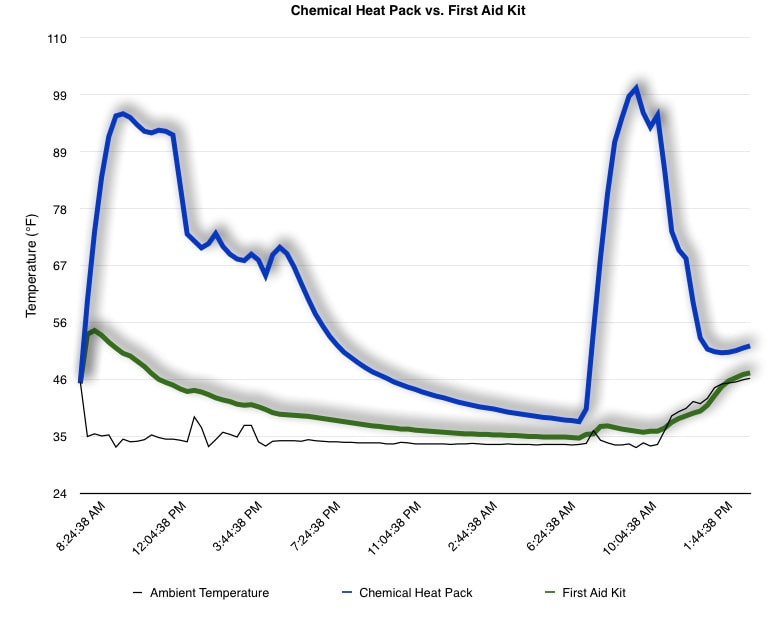

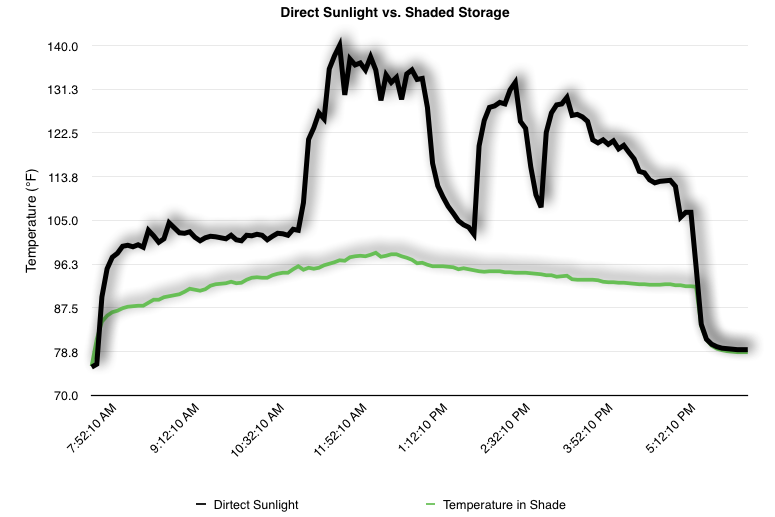

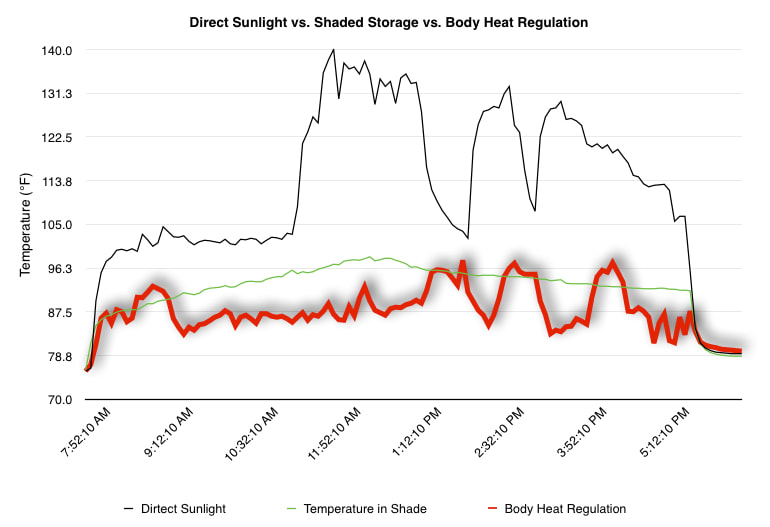

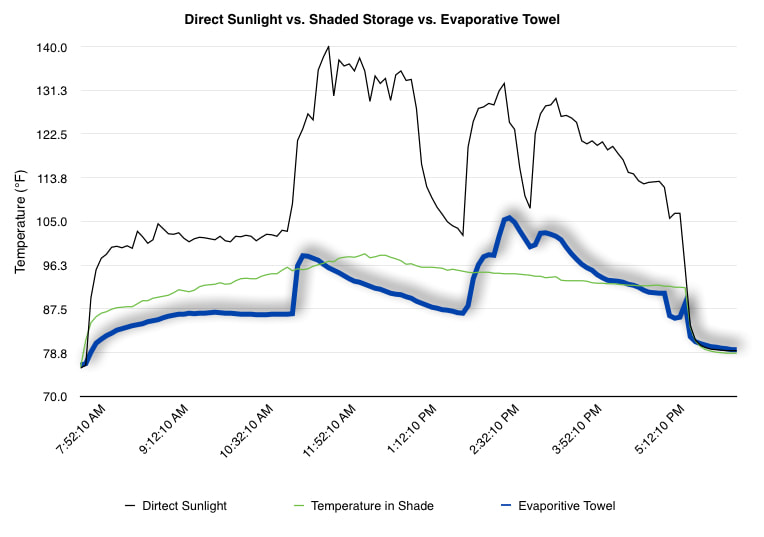

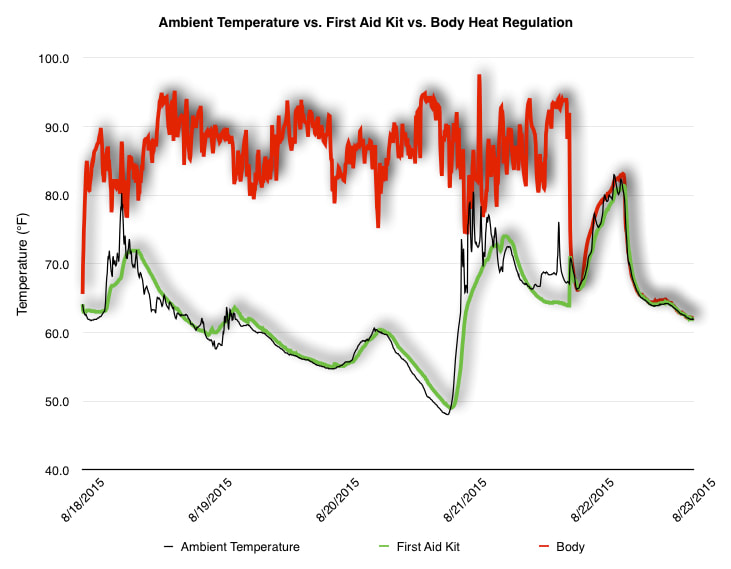

Throughout 2015, LWM has been studying potential storage options for temperature sensitive medications due to the variable temperatures experienced in remote environments. The research initially began as a result of a letter written by Mylan Specialty L.P., the manufacturer of EpiPen, to the Editor of the Journal of Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. In the letter, the author shared Mylan’s concern about the range of temperatures experienced by EpiPens while in remote environments. The letter reiterated the storage guidelines from the product's label as 68℉ to 77℉ with excursions permitted to 59℉ to 86℉*. Reality is that there are few places that many of us like to recreate where temperatures can meet the storage needs of epinephrine and other temperature sensitive medications. In recent years, research has been done both regarding the effectiveness of epinephrine after multiple freeze-thaw cycles** as well as the post expiration effectiveness of the medication***. Although these papers generally support the thought that epinephrine is better used (as prescribed) than not used even when out of date and post thaw, in an ideal situation individuals carrying temperature sensitive medication will limit the temperature extremes these medications experience while in the field. Goal of the Study LWM wanted to investigate low tech and easy to operate solutions to maintaining a relatively temperature stable environment where temperature sensitive medication or expedition equipment could be stored while in austere environments. The market has limited tools designed to manage temperature in remote environments that are functional to carry while on an outing or expedition. Of the storage devices available, the majority are marketed as insulin storage devices for people managing diabetes. Most of these systems rely on chemical cooling packs that are refrigerated and provide several hours of temperature stability. One exception is the Frio Insulin Cooling Case (http://www.frioinsulincoolingcase.com/) which uses evaporative cooling to keep medication cool in warm environments. While these devices do work to keep medications cool, they are not able to increase the temperature of a stored med. Hypothesis Prior to the testing, assumptions were that the human body provided the most consistent temperature in the non-climate controlled environment of an expedition. The hypothesis of the tests was storage of the medication near the body would allow for a consistent temperature. The study focused on temperature nearest the torso under insulating layers but above a base layer (for wearer comfort). It was unknown if the body’s evaporative process would reduce heat experienced by the object in cool environments Testing LogTag data loggers were used to conduct the temperature assessment, with the logger being treated as the temperature sensitive item (TRIX-8, http://www.logtagrecorders.com/products/trix-8.html). The loggers were calibrated at the time of purchase. During testing periods temperatures were taken at intervals between 5 and 20 minutes for the duration of each test. Tests ranged from 10 hours to 5 days in length, dependent on the environment and activity completed during the study. During each study period, several temperatures were logged to gain an accurate comparison. Temperatures measured included ambient, temperature within a first aid kit on site, and temperature at base layer of clothing. In some environments additional management tools were assessed, including an insulated thermos and chemical heat packs for cold environments and evaporative towels for cooling in hot environments. Cold Weather Results Five Day Winter Canoe Expedition Students from the 2015 LWM Medical Elective tested their low tech solutions for managing temperatures of medication during the expedition component of the elective. Tests were conducted on the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta in southern Alabama over a five day period in February. Temperatures were recorded at 20 minute intervals. Temperature of the first aid kit remained near the ambient temperature shortly after the start of the expedition, but avoided the spikes due to the insulative properties of the bag the kit was stored in. Body heat offered temperature stability within a small margin. Daily drops in the temperature noted in the data derived from the device kept on the body are assumed to be during clothing change. One of the other solutions offered by the students in the elective was a high end thermos that was used to insulate the logger from the environment. The thermos was brought inside the student's sleeping bag each night resulting in a rise in temperature; however the warmth was not retained during the day. An additional system assessed was storing the logger in a clothing pocket. The logger was wrapped in a small fleece towel, placed in a plastic bag, and stored in a jacket pocket. The result was cooler temperature than experienced in the direct body heat logger, but varied much more in temperature. This is potentially due to the changes in type/weight of the layer being worn by the tester due to varied ambient temperatures and resulting in varied insulation of the logger from environmental conditions. Winter SAR Training A winter survival training for a North Idaho based search and rescue group provided the environment for the second cold weather test. Temperatures were recorded at 20 minute intervals during the two day assessment. The tester wearing the logger that assessed body heat was consistently active during the testing period, participating in activities ranging from hiking with a full pack to building emergency shelters. In addition to ambient, first aid kit, and body heat temperature assessments, a logger was placed with a chemical heat pack within a simulated first aid kit. The chemical heat pack was opened, activated, and then placed in a winter hat inside the first aid kit. Warm Weather Results Grand Bay, Mississippi During an August LWM Wilderness First Aid course in Grand Bay, Mississippi, outside temperature was assessed in the sun and shade at 5 minute intervals in order to provide a comparison to cooling techniques. The logger in the direct sun was moved when it became shaded by shadows as the day passed. The dramatic decreases in temperature are a result of this short term shading. One of the test loggers was worn by a LWM instructor as a necklace in similar fashion to the tests completed in cold weather. The results of the test showed a noticeable cooling as compared to either the shade or direct sun exposure. Due to the nature of the course there were times where the instructor went inside while wearing the logger. Two of these times occurred in the afternoon and are noticeable drops. In addition to body heat regulation, the temperature inside an evaporative cooling towel (http://www.froggtoggs.com/cooling/the-chilly-pad/chilly-pad.html) was taken while placed in the sun. The cooling towel provides a similar environment to the Frio insulin cooling device mentioned above. Warming spikes in temperature are noted in the chart when the towel became dry. Cooling after the spikes was facilitated by dipping the towel in lukewarm water. Five Day Summer Backpacking Trip The final test in this series was completed on a five day backpacking trip on Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park. Assessments of ambient, body, and first aid kit were recorded at 15 minute intervals during four of the five days. During the test the tester was backpacking with a approximately 40 pound backpack at a moderate pace. The logger was kept in the tester's sleeping bag each night, but not attached to his body. Discussion There is no perfect solution to temperature management in remote environments, but with some effort, a level of temperature stability can be achieved. Using epinephrine as an example, there are several ways to work toward maintaining the 59-86 ℉ temperature range. Although slightly warmer than product labels recommend, regulation with body heat appears to be the best solution for cold weather trips. In mild temperatures as experienced during the Isle Royale trip, the best storage location, per the data received from the loggers, was the first aid kit. However, when planning for unknown temperatures, this study showed that body heat provided the most consistent temperature through a range of environmental temperatures. In hot weather environments, body heat storage temperatures remained relatively consistent, although higher than the EpiPen label recommends. The cooling towel proved the most comfortable option in the heat and was relatively consistent. However, as noted in the above study, there is the potential increased temperature if the evaporative material gets too dry. There are commercially available options designed specifically for the storage of epinephrine on the body that would provide relative comfort while on extended trips, including products such as the WaistPal (http://www.omaxcare.com/WaistPal.html). Temperature management is not the outright goal of these devices, but they would offer a comfortable, more temperature stable solution based on the findings listed above. A novel and low cost solution for an individual carrying multiple medications (e.g. a SAR medic or expedition doctor) could involve placing medication in a small organizer case and keeping the case in a holster device similar to those used for avalanche beacons. Avalanche beacon harnesses offer improved comfort while wearers are active and work well even when wearing a backpack. This would be more favorable then wearing a necklace, but does comes with space limitations. If traveling in hot environments, the medication organizer can be secured to the outside of a pack using a daisy chain or tactical MOLLE system after being wrapped in a evaporative towel. Conclusion This informal study begins a foundation for knowledge about the temperatures experienced by temperature sensitive medications in remote environments. The information above can be used to help make informed decisions on the storage of temperature sensitive medications in environments with variable temperatures. Additional considerations regarding temperature and storage include making storage decisions based on changing weather systems and temperature changes due to changes in elevation. Regardless of where medication is stored, it is most important to make sure that those who need to know where they can find it efficiently if it is needed. WM would like to thank to the following individuals for participation in the temperature study: Katie Cartier Carl Engelke Ben Dowdy Dave Ramsey Chris Buckley Wes Edmonds Katie Laycock David Nesbitt Tim Parker Lara Sancin Sources:

* Wolf, Ray A. (2014). Regarding the Use of Epinephrine Auto-injectors in Remote Settings. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 25 (4), 490. **Beasley, Heather, et.al., (2015). The Impact of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Epinephrine. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 26(1). 94 ***Simons, F.E., et. al., (2000) Outdated EpiPen and EpiPen Jr Autoinjectors: Past Their Prime? The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 105(5). 1025-30.

3 Comments

|

Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed